Words by Jono Beard

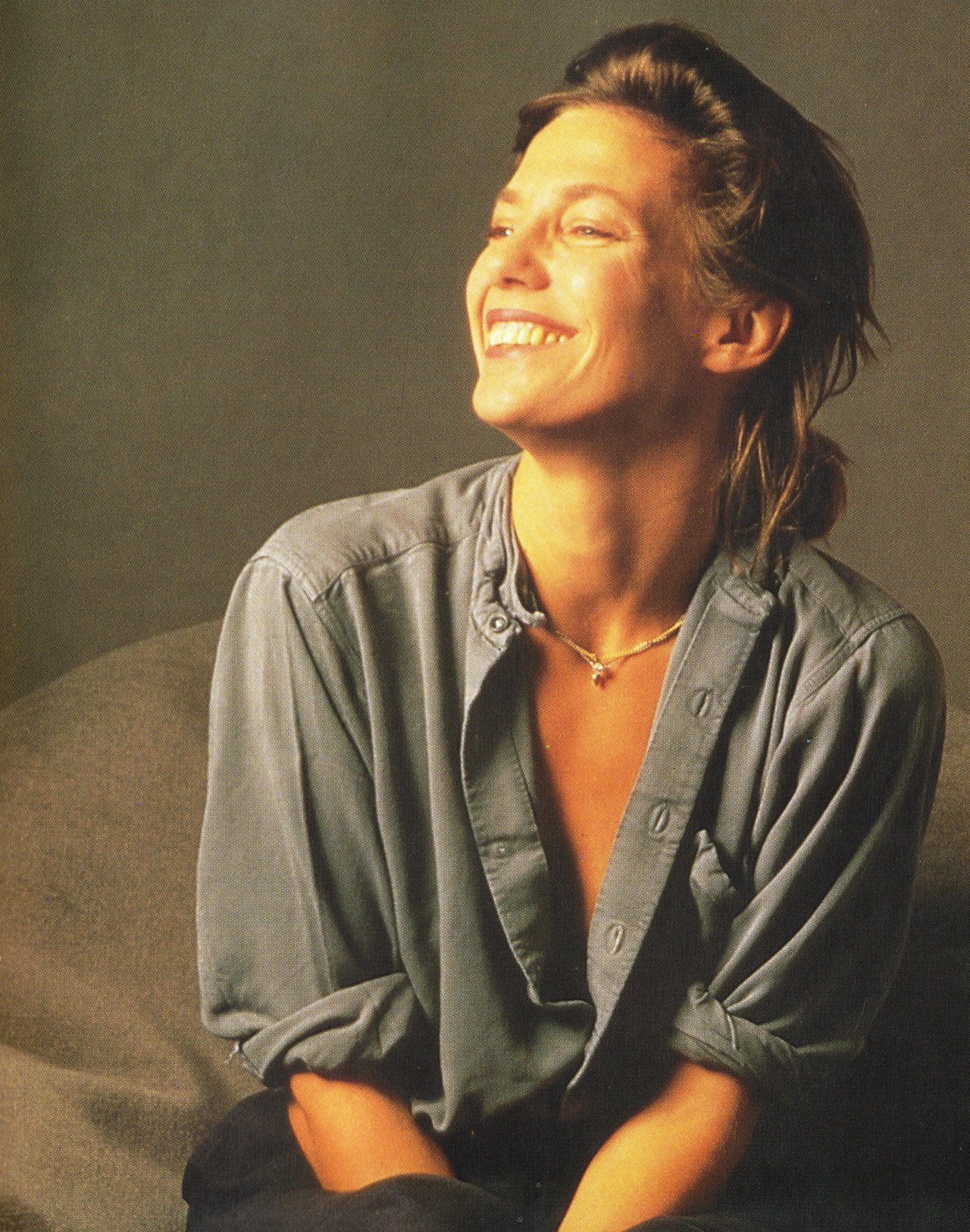

Jane Birkin was always a champion of her ex’s work, and her selflessness in the promotion of Serge Gainsbourg’s legacy has sometimes meant that her own has been overlooked. Her vocal influence is heard in pretty much every “sexy voiced” female singer to appear since the late 60s. From Donna Summer to Kylie Minogue to any pop star who’s faked an orgasm on record, they can all trace their lineage to Jane Birkin.

Having been interested in music for most of my life, I’m aware that I often tend to arrive at a fandom via what seems like a road less-travelled. For whatever psychological reason, I’ve always heavily gravitated towards music made by women - so for example, where most people might be very familiar with The Beatles and only know about Yoko Ono’s work in a tangential sense, it’s the opposite for me. I realise that this can appear wilfully contrary and a bit pretentious but it’s just what has always happened naturally in pursuit of my cultural interests. So, I’d like to talk a bit about Jane as a solo artist rather than just in tandem with Serge. Not because I think it’s a good exercise in redressing the balance somewhat (although that’s probably worthwhile too) but because I just know a lot more about her music for its own sake. Again due to where my knowledge lies, I’m going to focus primarily on her music as opposed to her status as a fashion icon, her acting and her activism. Embraced by France, she mostly sang in their language (like Petula Clark before her, her über-English accent became an asset), acted in French films and famously inspired the design of a French handbag. I don’t doubt that my appreciation for her work is hampered by the fact that I’m not fluent in French - not least because a lot of her songs were written by a man who never met a pun he didn’t like. I hope that this piece can serve as a brief overview of and introduction to her music for those who are interested.

Ah, “Je t’aime… moi non plus”. It barely needs writing about at this point in history. Neutered by parody and overuse, its first 20 seconds have become an aural byword for quaint Gallic sleaze, scoring antiquated comedic love scenes and grainy documentary footage about the sexual revolution. But Jane had long made peace with the fact that “When I die, that'll be the tune they play, as I go out feet first”. Its parent LP (surprisingly Jane & Serge’s only true duet credit) is nonetheless full of brilliant songs, my favourite being the Jane-only “Orang-outan”. The production of the album (ornate, lush, bass-heavy and just a little bit rough) proved ripe for sampling and cover versions by magpies of kitsch (meant affectionately) like Saint Etienne and Pizzicato Five. Incidentally, Jane Birkin seemed to be quite beloved in Japan, where what constitutes an attractive singing voice is sometimes less about technical ability and more about… I guess charisma, personality and, in women, cuteness. Jane’s wavering, breathy fragility was influential for a generation of future Japanese idols and her songs have been covered there more often than anywhere else, as far as I can tell.

The production on her first proper solo album, “Di Doo Dah” smooths out some rough edges for better or worse and lays Birkin’s voice atop twangy guitars and gently symphonic string arrangements. 1975’s follow-up “Lolita Go Home” is a much more interesting album for me. The feather-light disco of the title track is followed by Gainsbourg originals and hazy, dreamlike covers of jazz standards from the 30s. The next year, she appeared as the main character in a film also called “Je t’aime moi non plus”, written and directed by Serge. The film’s commentaries on the fluidity of gender and sexuality are complicated (ahead of their time in some ways and backwards in others) so it’s best if I just mention that its Birkin sung theme “Ballade de Johnny-Jane” is really good.

1978’s “ex fan des sixties” is my absolute favourite of all her albums. It’s quite varied in its production and songwriting - at times tongue-in-cheek and playful and at others very poignant and sentimental. Unlike a lot of albums, it really hits its stride in its second half. Gainsbourg wrote every song, and “Dépressive” (melodically based on Beethoven’s "Sonate n°8, Opus 13”) is one of the best of his many Classical music-aping pieces.

It’s followed by the ghostly “Le Velours Des Vierges” (above), which wouldn’t sound out of place on an Emmanuelle Parrenin album. “Classée X” is deceptively gentle and catchy and Jane almost rocks out on album closer “Mélo Mélo”. I’ve always loved how front-and-centre her voice is in the mix, particularly on that song. A producer with more mainstream sensibilities might have been tempted to bury it low with an abundance of echo and stifling chorus effects, but producer Philippe Lerichomme recognised that wavering, breathy fragility I mentioned before as unquestionably vital to the sound and character of these songs.

The production on her next 3 albums suffers ever-so-slightly from a creeping, unavoidable 80s-ness, from which it seemed no artist could fully escape. The songs start to become a little dated by funky slapped bass, reverbed kick drums and that one electric piano sound that everyone seemed to use for a while. Your mileage may vary on how much this bothers or delights you, but I guess they lack a certain timeless quality. Nevertheless, songs like “Baby Alone in Babylone” (based on the 3rd movement of Brahms’ 3rd Symphony), non-album single “Quoi”, “Être ou ne pas naître” and “Lost Song” are all masterpieces of French pop from the period.

Despite their divorce in 1980, Gainsbourg continued to write for Birkin, which lends an interesting subtext and pensive tension to the albums “Baby Alone in Babylone”, “Lost Song” and “Amour Des Feintes”. She also recorded her first of several well-received live albums in 1987. Gainsbourg died of a heart attack in 1991 and Jane’s next album wouldn’t appear until 1996. “Versions Jane” featured covers of songs Gainsbourg hadn’t necessarily written for her and served as a loving tribute to his artistry. This album marked a development to a more interesting, organic and effortlessly cool production style which was, I feel, an important step in securing her own musical legacy. The grungy guitars of “Élisa'' contrast comfortably with the café jazz of “Ce Mortel Ennui”. Tribal drums, brass bands, Middle Eastern dulcimers and arabesque string arrangements populate the rest of the album. Her fantastic 2002 live album “Arabesque'' would hone in somewhat on this musical aesthetic.

“À La Légère”, from 1999, was Birkin’s first album to feature no Gainsbourg credits and instead contains collaborations with other members of French music royalty like Étienne Daho and Françoise Hardy along with younger artists like MC Solaar and Zazie. Again, she continued to solidify her cool reputation without sacrificing brilliant pop songs like the title track and “Les Clés du Paradis”. It must have sounded very modern at the time but now reeks of the late 90s in a way I never imagined something could. I don’t think I mean that as a criticism, however.

Her next album, “Rendez-vous”, continued the collaborative theme but with a more understated production style. The list of collaborators alone should make you want to listen to this album; we’ve got Hardy and Daho again, but also Beth Gibbons of Portishead, Caetano Veloso, Yōsuie Inoue, Bryan Ferry and Feist. The beautiful “Fictions” followed in 2006, and was her first and only predominantly English-language album. “My Secret” is a rare Beth Gibbons original, there’s a rarer still (and excellent) cover of Kate Bush’s “Mother Stands For Comfort” and what I would consider the definitive version of Neil Young’s “Harvest Moon”. This album is a really good introduction to Jane Birkin if you have no knowledge of French or are already a fan of daughter Charlotte Gainsbourg’s music. On her next album, “Enfants d’hiver”, Birkin wrote or co-wrote all of the songs for the first time, and the results are mostly charming and affecting. There’s also an interesting song about the Burmese politician Aung San Suu Kyi, whose legacy has grown more complicated since that track’s writing and release.

Almost a decade would pass before her next album “Birkin/Gainsbourg : Le Symphonique”. Not dissimilar in its execution to “Versions Jane” but with a wider scope of oeuvre, it sets Serge’s songs and Jane’s voice to stately, cinematic string arrangements that serve both extremely well, if safely. At the time, it seemed very much like a career-encompassing “final album” to me and I wouldn’t have been surprised if it had been.

What became her actual final album was 2020’s “Oh! Pardon tu dormais…”. Like on “Enfants d’hiver”, Jane wrote or co-wrote all of the songs, this time in collaboration with Étienne Daho and Jean-Louis Piérot. Although there is a retrospective tone (the album is named after a TV movie written and directed by Birkin in 1992) and although grief is a theme (the subject of death is present on several songs, likely informed by the death of her daughter - photographer Kate Barry - in 2013), the album never feels heavy or depressing (video at bottom of page). There’s a mellow lightness and unfailing classiness to the production, which intentionally pays homage to her work in the 60s and 70s with its bass-heavy backbone and symphonic string arrangements. Her voice, while slightly deeper and more controlled, is surprisingly unchanged. She certainly doesn’t sound like someone who’s going to pass away in 3 years. But I suppose a lot can happen to a person’s life and health in 3 years. She doesn’t sound, artistically, like someone who’s just made her last album. But her last album is what it turned out to be, and it’s a wonderfully dignified high note of her career and a worthy epilogue to her life in music.